“Il y a des complicités, des amis… Theresa von Trattner, une élève au piano chez qui il habite. Elle est mariée, mais c’est à elle que Wolfgang fait le cadeau le plus significatif : la grande Sonate en ut mineur K 457 et la Fantaisie dans la même tonalité, K 475. Une passion, celle-là, il suffit d’écouter ce que dit sérieusement la musique. C’est un des grands chefs-d’œuvre de Mozart, un véritable roman pour piano, emporté, tragique. Les deux œuvres sont dédiées à Theresa. Mozart les lui a données avec des lettres d’accompagnement sur la manière de les interpréter ; les lettres, Theresa, plus tard, refusera de les communiquer à Constance. Wolfgang et Theresa ont été beaucoup au clavier côte à côte. La musique est ici exaltée, frémissante, sombre, très large, elle parle de bien des choses qui se sont passées entre les touches. N’oublie pas ce jour, c’était l’été, j’étais à gauche, toi à droite, on plongeait, on se veloutait, je te soutenais, je te poussais, je te recevais en douceur, je revois tout, les rideaux, le tapis, les meubles, la lumière venant caresser le piano. Le magnétisme jouait à notre place, ah, je connais bien ce violet…”

(Philippe Sollers – Mystérieux Mozart)

A little fantasy never hurt anyone. So…

Therese von Trattner, Mozart’s Euterpe for the Piano Sonata and Fantasia in C minor, young, beautiful and a very gifted pianist. Wife of Johann Thomas von Trattner, the leading music publisher and retailer in Vienna between 1770 and 1790, Maria Theresia von Trattner was forty years younger than her husband. In 1751 Johann von Trattner had become court bookseller and in 1754 court printer, then official publisher of schoolbooks for the Austrian Empire. The privileges resulting from Empress Maria Theresa’s patronage and his own efficiency as an entrepreneur helped his firm to flourish. In 1773 he bought the Freisingerhof on the Graben and built Trattnerhof there, in 1777.

The Trattnerhof became the most famous address in all Vienna. The building had such unusual dimension (for the times) that it even included a concert hall. This proved to be a very interesting prospect for Mozart – he was planning to present a concert series of his own, for which the piano would not have to be taken out of the house.

“On the ground floor of the Trattnerhof were businesses (among them one of Trattner’s own bookshops, lavishly appointed in marble), storerooms, stalls and outbuildings leading back to the two inner courtyards. Five separate staircases provided access to the residential quarters, wyich accomodated roughly 600 people. The cost of the entire edifice, with its splendidly ornate furnishings – including giant caryatids at the portal and a balustrade of sculpted figures on the balcony – was around 390 000 florins. The style of this controversial structure made no secret of Trattner’s standing as a nouveau riche who created his own private mythology and proudly displayed what he had achieved through his business acumen. It was in total contrast to the restrained elegance of the aristocratic palaces that served as its model. Contemporaries were divided in their opinions: some were impressed by the building’s dimensions and by the sheer financial boldness it represented, while others found it in poor taste.” (Volkmar Braunbehrens – Mozart in Vienna)

The story of Mozart’s Trattnerhof is best told by Dr Michael Lorenz in his fascinating article: “Mozart in the Trattnerhof”. Michael Lorenz has a great gift for bringing history to life! To read through his extraordinary work, so masterly researched and written, is to embark in a travel through time, with history coming alive at each step. So… go to his scholarly journal to learn about Mozart’s Trattnerhof, how he lived there, how he performed there, to read the documented history of that special building, to see images of the place (most of them never before published), the plan of Mozart’s apartment, and also of Trattner’s apartment (where Mozart played in a private concert for Therese von Trattner in May 1784), the list of subscribers to his concerts as he sent it to father Leopold, the earliest existing photograph of the Trattnerhof, taken in 1875, the second entrance of the Trattnerhof at Graben 29A in 1910 (the door that Mozart had to pass to get to his apartment), and many other fascinating images and documents. History will come alive as you read, as you look at the images, so prepare for a wonderful Travel in Time!

http://michaelorenz.blogspot.ro/2013/09/mozart-in-trattnerhof.html

It was here, Am Graben no. 591-596 in the inner city, that Mozart moved on 23 January 1784, and stayed until 29 September of the same year. The three famous subscription concerts which Mozart gave here in March presented the Viennese audience with his three new piano concertos – likely K 449, K450 and K451. Here he continued to give piano lessons to Theresa, who had been his pupil since December 1781, and who may have been involved in the concerts as the organizer, just as she reportedly was in the academies. And it was here where the beautiful C minor Sonata was born, which in October 1784 he dedicated to Theresa – just as he did with the C minor Fantasia, a few months later.

Compositions in minor keys are rare in Mozart’s works. The Piano Sonata No 14 in C minor is only one of two sonatas Mozart wrote in the minor key (the other one being the great Piano Sonata no 8 in A minor K.310). Musicologists say that Mozart was extremely deliberate in choosing tonalities for his compositions; therefore, his choice of C minor for this sonata may imply that this piece was perhaps a very personal work.

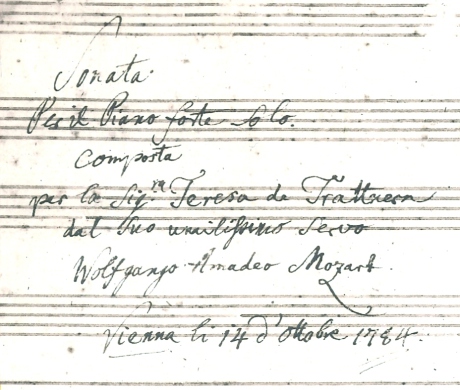

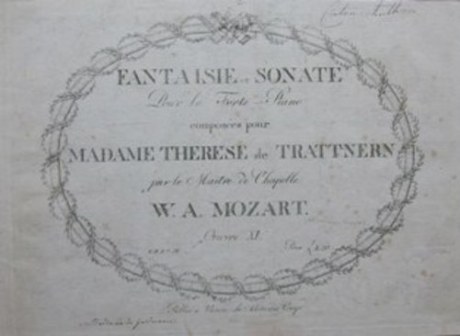

The Piano Sonata No. 14 in C minor, K. 457, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was composed and completed in 1784, with the official date of completion recorded as October 14, 1784 in Mozart’s private catalogue of works. It was published in December of 1785 together with the Fantasy in C minor, K. 475, as Opus 11, by the publishing firm Artaria, Mozart’s main Viennese publisher. And the title page bore a dedication to Therese von Trattner:

“Sonata. Per il Piano forte solo. Composta per la Sig-ra Teresa de Trattnern dal suo umilissimo servo Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart. Vienna li 14 d’Ottobre 1784.”

Of this sonata, Köchel said: “Without question, this is the most important of all Mozart’s pianoforte sonatas. Surpassing all the others by reason of the fire and passion which, to its last note, breathes through it, it foreshadows the pianoforte sonata, as it was destined to become in the hands of Beethoven.”

Fire and passion for a pupil? Maybe… or maybe not… Maybe Theresa was not just one of Wolfgang’s pupils. Fire and passion which, to its last note, breathes through the music written for, and dedicated to, a beautiful, talented and very special woman…

“Fantaisie et Sonate pour le Forte-Piano composées pour Madame Therese de Trattnern par le Maitre de Chappelle W.A. Mozart”

The 1785 engraved edition makes no secret of the dedicatee. But the two masterpieces are not only dedicated to Therese, they were composed for Therese. So says the Master himself. More, the composer offered his pupil two letters in which he explained how the works should be interpreted. Was this something he did for all his pupils? After Mozart’s death, Constanze, who knew of their existence, asked Therese to hand her the letters, but Therese refused. She never said why. Were there only musical instructions on those precious pages? Therese wouldn’t have had any reason to not let them be known. Yet she refused to renounce the letters – and not even the long years of friendship between the Mozarts and the Trattners would make her change her mind. Theresa kept the letters for herself. Could Phillipe Sollers’ fantasy be an answer?

“…il suffit d’écouter ce que dit sérieusement la musique… Wolfgang et Theresa ont été beaucoup au clavier côte à côte. La musique est ici exaltée, frémissante, sombre, très large, elle parle de bien des choses qui se sont passées entre les touches. N’oublie pas ce jour, c’était l’été, j’étais à gauche, toi à droite, on plongeait, on se veloutait, je te soutenais, je te poussais, je te recevais en douceur, je revois tout, les rideaux, le tapis, les meubles, la lumière venant caresser le piano. Le magnétisme jouait à notre place, ah, je connais bien ce violet…”

“Mozart’s masterly C-minor Sonata bears this handwritten dedication: “Sonata. For Piano solo. Composed for Mrs. Theresa von Trattner by her most humble servant Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Vienna, 14 October 1784.” It remains a generous tribute to his talented twenty-six-year-old pupil, the wife of a Viennese book publisher and entrepreneur. To add to its power, Mozart himself prefaced it with a fantasia in the same key, completed seven months later, in May 1784…” “This fantasia is so complete in itself that it is difficult to think of it as a “prelude,” although Mozart published it together with the C-minor sonata, K. 457, that he had written in the previous year. It contains five sections: Adagio, Allegro, Andantino, Più Allegro, and Tempo I, in the last of which the opening Adagio returns in a relentless form to round off the whole piece.” (Neal Zaslaw: The Compleat Mozart)

Born in 1758, Therese von Trattner died in 1793, aged 35 years. Two years younger than Mozart, she survived him two years, only to reach the age which he himself had reached on earth. When she left she took Mozart’s letters with her. The Trattnerhof was demolished in 1911 and replaced by two ordinary buildings. That special place where Mozart lived and loved, composed and played, is gone, but the Sonata and Fantasia in C minor have travelled through time, bearing within them the mystery, the fire, the passion…

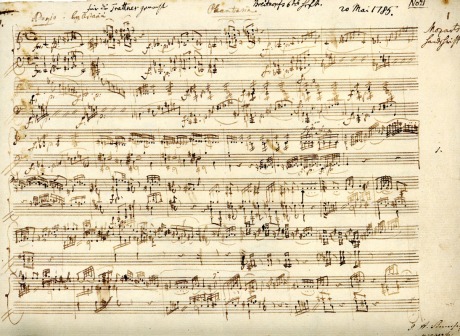

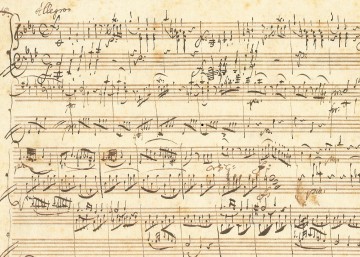

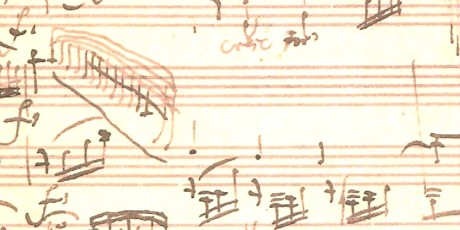

An original autograph of the two pieces was rediscovered in 1990 at the Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Philadelphia by Judith DiBona, an amateur pianist and accounting manager at Eastern’s sister school. Eugene K. Wolf at the University of Pennsylvania was contacted to identify and authenticate the manuscripts. He emerged with findings concerning the time of composition between the movements of the sonata and the fantasy, which were published in The Journal of Musicology in 1992. First, his findings further confirmed that the Fantasy and Sonata were written independently due to differences of stave spans, paper-types, and even ink color in between the two manuscripts. Wolf also found differences in paper types between the first and third movements of the sonata and the second Adagio movement, which implies that the second movement was written down at a separate time from the rest of the sonata. He theorizes that the second movement was composed the earliest as an instructional piece for Thérèse von Trattner. Since the second movement is in rondo form and slower than the others, it could exist independently from the sonata more easily than the other movements. (source: wiki)

“Mozart uses the key of C minor to reflect a tragic and troubled mood. Both the somber Sonata and the introductory Fantasia are unprecedented in scope and depth of feeling. Even though Mozart published them together, each work is complete unto itself and independent of the other for contrast and intensity. The Fantasia is somewhat Schubertian in its modulations, and provides a glimpse of Mozart’s improvisational powers. The Sonata is probably the most impassioned of all Mozart sonatas, and a clear model for Beethoven’s Op. 13 Pathétique Sonata of 1799, also in C minor.”

“The Sonata opens with a Mannheim-rocket figure which propels it forward. This is the figure Mozart uses with abandon in his great G minor Symphony. The first and the third movements are both dark and dramatic. The beautiful Adagio movement in E flat major provides the requisite contrast between the troubled outer movements.”

“Grim seriousness reigns in K. 457” writes Alfred Einstein, “it is clear that it represents a moment of great agitation, agitation that could no longer be expressed in the fatalistic A minor key of the Paris Sonata, but requires the pathetic C minor that was to be Beethoven’s favorite key for the expression of similar emotions. It has rightly been said that this work contains a ‘Beethovenisme d’avant la lettre.’ Indeed it must be stated that this very Sonata contributed a great deal towards making ‘Beethovenisme’ possible.”

“Contrasting with the concentrated first and last movements, there is a broad concerto-like Adagio in the tranquil key of E-flat major, which, in accordance with the true nature of its creator, who could not seek any easy way out, does not lead to a finale in major, on the contrary, the Finale is just as pathetic as the first movement, and even darker. There is a disproportion in this work. The sonata form of 1784 is too small for the expansion of feeling, although we must admit that one of the most powerful reasons for the effectiveness of the work is precisely the explosive compression and brevity of the first and last movements.”

“Mozart himself must have felt the necessity of providing a basis for the explosive quality of the sonata, and justifying it as the product of a particular spiritual state; accordingly, he preceded it with the Fantasy, K. 475 (written on 20 May 1785), and published the two together. This fantasy, which gives us the truest picture of Mozart’s mighty power of improvisation – his ability to indulge in the greatest freedom and boldness of imagination, the most extreme contrast of ideas, the most uninhibited variety of lyrical and virtuoso elements, while yet preserving structural Logic – this work is so rich that it threatens to eclipse the sonata, without actually doing so. It is the key to understanding of Mozart’s other fantasies.”

(source: Zeynep Ucbasaran)

MOZART’S PIANO SONATA IN C MINOR ON FORTEPIANO

MOZART’S FANTASIA IN C MINOR ON FORTEPIANO