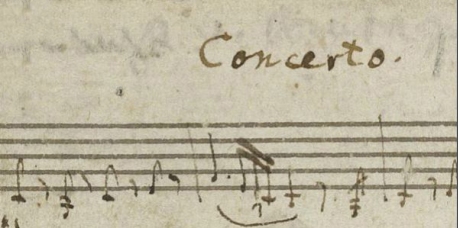

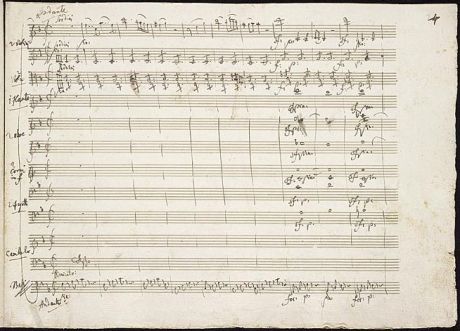

“the 9th of March

A Piano concerto. Accompaniment: 2 violins, 2 violas, 1 flute, 2 oboes. 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 clarinets, timpani and bass.”

It is the entry in Mozart’s hand-written catalogue of works, anouncing the splendid Piano Concerto in C Major, no 21, K.467!

On the 10th of March 1785, less than one month after the premiere of the stormy, moving, dramatic D minor, Mozart was presenting another piano concerto to the Viennese audience: calm, brilliant, full of light and joy, majestic in its great beauty!

As with the Piano Concerto in D minor, the C Major Piano Concerto was composed for the series of Lenten subscription concerts that Mozart was giving in 1785. Leopold Mozart, who had come to visit his son just in time to witness the premiere of Mozart’s sublime D minor Piano Concerto, would write to Nannerl: “We never get to bed before one o’clock and I never get up before nine. We lunch at two or half past. The weather is terrible. Every day there are concerts; and the whole time is given up to teaching music, composing and so forth. I feel rather out of it. If only all the concerts were over! It is impossible for me to describe the rush and bustle. Since my arrival your brother’s fortepiano has been taken at least a dozen times to the theater or to some other house…” Father and son went out together, to eat of attend musical or social events, or received friends in Mozart’s apartment, where they would spend hours making music; in the same time the composer went on with the lessons with his pupils, took part in various public and private concerts and, above all, composed!

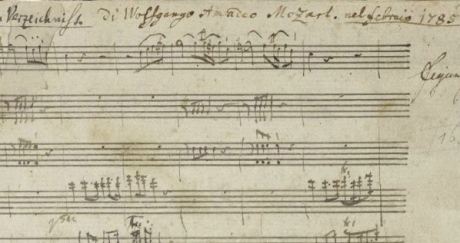

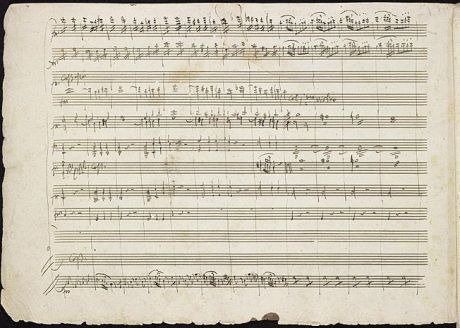

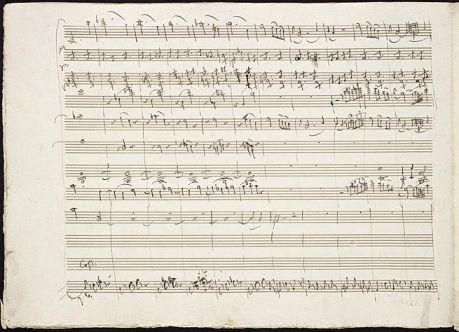

Mozart entered the C Major Piano Concerto in his catalogue on 9 March 1785 (although on the autograph score he writes “in February 1785” – “Concerto di Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart, nel Febraio 1785”), and premiered it on 10 March 1785 at the Burgtheater – The National Court Theater, in a concert for his own benefit.

A handbill for the concert announced that it would include “a new, just finished Fortepiano Concerto”, in addition to Mozart playing improvisations employing “an especially large Fortepiano pedal”.

“On Thursday, March 10, 1785, Kapellmeister Mozart will have the honor of giving in the Imperial and Royal Court Theater a Grand Musical Concert for his own benefit including not only a new, just finished fortepiano concerto to be played by him, but also an especially large fortepiano pedale in improvising will be used. The remaining pieces will be announced by a large poster on the day of the concert.”

A letter from Johann Samuel Liedemann, a merchant in Vienna, from 18 February 1785, states that “…the Fortepiano maker Walther had augmented his Fortepiano with a Pedal. Mozart played the instrument and it produced a wonderful effect” (he is referring to the premiere of the D minor Piano Concerto of 11 February 1785). Leopold’s letter to Nannerl and the announcement for the Burgtheater concert of March 10 indicate Mozart also played the C Major Piano Concerto on a piano which had a special pedal attachment: “He has had a large fortepiano pedal made, which stands under the instrument and is about two feet longer and extremely heavy”. The success of the concert and the receipts of 559 florins were reported by Leopold with satisfaction and pride to his daughter, in the letter of 12 March 1785.

“This concerto followed the last at four weeks interval. Between the two there is absolute contrast. On one hand, passion, conflict, storm of the spirit; on the other, calm and majesty. We have already noted how, more than once, Mozart produces, one after the other, two first-rate works of highly contrasted inspiration: the autumn before, with the concerto in B flat, K.456, and the sonata in C minor; in 1786, with the concertos in A and C minor; and again in 1787 and 1788 with the quintets and symphonies in G minor and C. We said that it was but one manifestation of his very mobile nature, ready to leap without transition from one aspect of reality to another, from one mood to its opposite. Sometimes the sorrowful work precedes the joyful one; sometimes the contrary. In February and March, 1785, the order is optimistic: the song of peace comes after the tempest; the luminous C major exorcises the sombre and daimonisch D minor. Nevertheless, the concerto in C is not a blithe work; it is powerful and motionless rather than joyful, and in its immobility we recognize, albeit frozen, the billows of the D minor. (Cuthbert Girdlestone)

The C Major’s first movement, the ‘Allegro’, is (not in the autograph but in all editions), “Maestoso” in its design and essence! The second movement, ‘Andante’, breathtakingly beautiful! The last movement, ‘Allegro vivace assai’, light, airy, wonderful! On the 10th of March, 1785, at the Burgtheater, could this have been the sound that the musicians and audience delighted in?

“The first movement is headed maestoso, a mark which should be observed and not replaced in practice by brillante, as is done by some musicians who consider they know what Mozart wanted better than Mozart himself. But the first subject, as we hear it in the first eleven bars, belies this indication. It is a march like so many first subjects in concertos of the period, but a tiptoed march, in stocking feet, and even when woodwind, brass and drums interrupt the stringgs, it does not rise above piano. It is almost a comedy motif and we should not be surprised to see Leporello emerge from it. But this impression is soon rectified. Conforming to the plan of the quiet beginning followed by a forte, Mozart repeats the theme with all the resources of his orchestra, modulates at once with unusual freedom and, passing quickly through A minor and C minor, settles a while in G major on a tonic pedal. (…) After giving out these two themes, it would seem that the tutti had but to conclude and admit the solo. But this concerto does not act like its predecessors. Instead of a closing figure, the march begins again, first in imitations in the strings, piano, then, when all the orchestra has joined in, forte, and the music launches forth into a working-out whose progress, led with a steady step and insistent in its regularity, reminds us of the straining and pitiless vigour of the D minor. There is no modulating; everything comes down, in the last resort, to rises and falls of one octave, repeated several times, without haste, now with the whole orchestra, now antiphonally, with strings and woodwind. Such calm perseverance is irresistible; its strength is in its mass, not in its fire or speed (on condition, once again, that the movement is taken at a moderate speed and even heavily, maestoso, and not brillante. Played swiftly and lightly, this passage becomes a kind of breathless race that keeps on coming back to its starting-point, which is nonsense); the music looks neither right nor left; its progress is due to singleness of will. No passage demonstrates better than this both the kinship and the ontrast which unite and separate the twin concertos; in one, vehemence and wrath; in the other, self-assurance; in both, a will firm and inexorable.” (Cuthbert Girdlestone)

“In neither of Mozart’s earlier works do we find the contrapuntal potential of the opening so fully realized on the larger structural level as it is in K.567, where various polyphonic settings of the opening theme produce some of the main structural blocks of the ritornello. (…) Charles Rosen has described K.467 as “Mozart’s first true essay in orchestral grandeur” and has commented on the block-like nature of its construction…”

And the ‘Andante’ that follows… Mozart’s fragile, beautiful soul, transfigured into Music!

“The world of the andante is that of the “dream” andantes, a family which comprises some of Mozart’s most beautiful slow movements in earlier years and in the long successions of which it is the last; but its form is unique. It is a piano cantilena preceded by a tutti prelude and sumptuously sustained and adorned by the murmur of the strings and the multi-coloured raiment of the wind. The tune winds from key to key, smooth and closely blended; it passes through various moods, some dreamy, some full of anguish, some serene, but the themes hardly stand out; it is a river, moving slowly but unceasingly, and only from time to time does an eddy in the current announce a freshy subject. Yet it is not a fantasia. There is directions and progress in its emotion and its form. The stream advances, turns back, passes on again, and though its structure be free, it is never loose. (…) And all the time it never stops singing; one feels that its chief contribution here is its tone colour, the pale, delicate colour of the 1780 piano, whose beauty Mozart never set forth more felicitously than in this nocturne. We say, nocturne, and in truth the rapprochement with Chopin can hardly be avoided. he hazy atmosphere of the mutes, the quivering calm of the ceaseless triplets, the slow, sustained song of the piano—more than all this, the veiled and sorrowfully passionate soul which this music expresses with such immediacy, do we not find them in the work of Chopin and especially in those nocturnes of which the “dream” of Mozart’s reminds us? This Andante, so placid at first hearing, betrays on further acquaintance an agitated mood. Its perpetual instability, to which its constant modulating and its unsatisfied quest for new places bears witness; its morbid disquiet, thinly concealed now and again under an appearance of calm, breaking forth with heart-rending pathos in the chromaticisms and the discreet yet pungent hues of ex.270 are unquestionably fundamental elements of Mozart’s nature, but they are elements which he shares with Chopin.” (Cuthbert Girdlestone)

To our ears, to our heart, the ‘Andante’ of Mozart’s C Major Piano Concerto no 21 is perfect beauty as it is: a ‘simple’ melody that moves us to tears whenever we listen to it. We don’t even want to imagine it changed in any way – and the only way in which we would probably accept it changed would be to listen to Mozart himself playing it. Philipp Karl, an amateur-musician who had heard Mozart perform two of his piano concertos in Frankurt, in October 1790, later reported that when Mozart played the slow movements of his piano concertos he embellished them “tenderly and tastefully once one way, once differently, following the momentary inspiration of his genius”. In 1803 Phillip Karl published embellished versions of six Mozart piano concerto slow movements (K.467, K.482, K.488, K.491, K.503 and K.595), presumably inspired by his contact with Mozart, but not imitative of the composer’s own improvisations.”

“The andante occupies a world apart, a sonic dream world evoked by the magical effect of muted and pizzicato strings. It offers moments of sublime beauty and ends in a state of bliss, but its surface serenity cannot conceal the turmoil that lies beneath. At every turn there is a poignant reminder that happiness is transient, its promise easily revoked. And the escape to a dream world is consummated only in the imagination.” (David Grayson)

How might that evening of 10 March 1785 have looked like? Here’s what David Grayson tells us in his book “Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 20 and 21”:

“Iconographic evidence suggests that in “halls” like the Mehlgrube the players would probably have occupied a low platform situated not at the end of the room, but against one of the long walls. The seating plan for K.466 would probably have been similar to the one recommended in 1802 by the piano-maker and Mozart pupil Nannette Stein Streicher:

“In performing concertos, especially Mozart’s, one should move the fortepiano several feet nearer (the audience) than the orchestra is. Directly behind the piano leave just the violins. The bass-line and wind instruments should be further back, the latter more than the former.”

Adalbert Gyrowetz, one of whose symphonies was programmed in Mozart’s Mehlgrube series, noted in his presumed autobiography that Mozart had hired a “full theater orchestra” for these concerts. This was most likely the orchestra of the Burgtheater, where, four days later, on 15 February 1785, Mozart again played the D-minor Piano Concerto, in a concert given by the singer Elisabeth Distler.

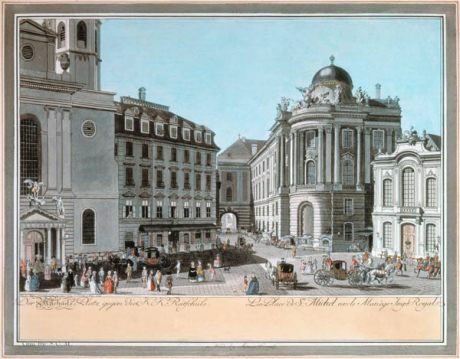

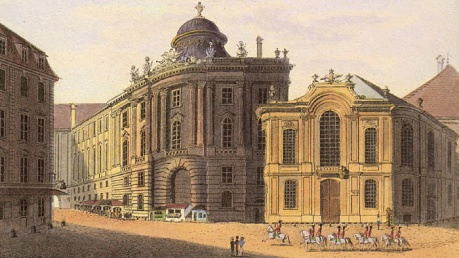

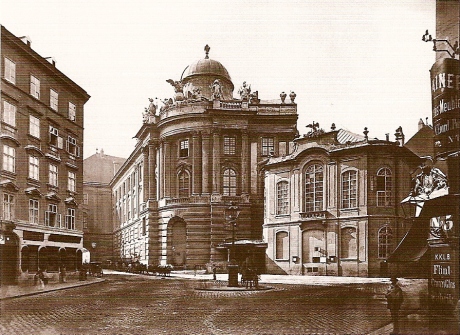

The Burgtheater, representing the third category of concert venue, was also the site of the premiere of the Piano Concerto in C, K.467, less than a month later, on 10 March 1785. Located on the Michaelerplatz, the Burgtheater was built in 1741 and renovated numerous times before its closing in 1888. Plans reflecting the state of the building during the 1780s show an oval-shaped house, with seating on the floor divided into two sections, ostensibly according to the social rank of the spectators: the Noble Parquet in front, and behind it the slightly elevated Second Parquet, with rows of benches and standing rooms at the rear. (Social segregation was not complete, however, as individuals connected to the theater, including composers and performers, could obtain passes granting admission to the Noble Parquet.) Four balconies surrounded the floor. The lower two held the boxes rented on an annual basis by the nobility, plus, in the first tier, one box overlooking the stage, reserved for the director, and three “Imperial loges” (one in the center and two on the right) overlooking the orchestra, which occupied the floor at the front of the stage. The upper two balconies were galleries with benches and standing room. When jam-packed, the Burgtheater may have accomodated as many as 1800 spectators, but most estimates of the audience capacity are much lower, ranging from around 1000 to 1350.

According to a Vienna theater almanac of 1782, the Burgtheater orchestra comprised 35 players: six first and six second violins, four violas, three cellos, three basses, pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets, and one timpanist. Assuming that these figures are also reliable for 1785, that the full theater orchestra participated in Mozart’s concerts in both the Burgtheater and the Mehlgrube, and that the entire ensemble was used for the concerto accompaniments, we can conclude that the orchestra for the first performances of K.466 and 467 consisted of around 32 players (one of the flutes and the two clarinets not being needed). (…)

Richard Maunder has speculated that, when Mozart performed his piano concertos in the theater, the orchestra may hav been in the pit, while he alone occupied the stage. Putting the soloist in this privileged position, Maunder reasoned, would have helped solve potential balance problems between the fortepiano and the orchestra, whose players would have been seated facing the stage, with their backs to the audience. Such a “theatrical staging” of the concerto moreover made manifest the genre’s affinity with the operatic aria. Daniel Heartz, however, has offered evidence that it was customary for Lenten concert and oratorio performances at the Burgtheater to follow the Italian practice and have all of the musicians on stage: the orchestra, soloists and chorus. He speculated, though, that the arrangement described by maunder might have been a practical necessity at other times of year, when theater rehearsals and stage sets might have made it difficult to rearrange the stage for an orchestra. Mary Sue Morrow has challenged this reasoning, arguing that rehearsals were often held elsewhere and that the theater’s repertory system would have required that the sets be struck after each performance anyway. Maunder’s theory seems unlikely from a purely logistical point of view, given th mixed nature of Mozart’s typical concert programs. For example, his concert of 23 march 1782 at the Burgtheater began and ended with movements of the “Haffner” Symphony, with arias, concertos, concertante movements, and solo piano works interspersed in between. It would have seeed odd for the orchestra to start the program on stage, then repair to the pit, only to re-ascend at the end of the concert for the “haffner” finale. Even odder would have been for the orchestra to remain in the pit throughout, leaving the audience to face an empty stage at the start and conclusion of the evening. For performances of Mozart’s concertos in the theater, then, we may imagine all of the performers on stage, arranged according to the seating plan recommended above by nannette Stein Stricher.” (David Grayson – Mozart: Piano Concertos Nos. 20 and 21 – “Performance practice issues”)

A look at the Burgtheater through time – that Burgtheater where Mozart premiered his piano concertos and operas:

In 1888 the “old” Burgtheater was demolished, and a new building with the same name was built on the Ringstrasse: the new Burgtheater. The theater where Mozart premiered his masterpieces had to make space for… space… Almost all the places where he had lived and composed were torn down without the smallest thought that those were not just buildings, they were places of history which should have been preserved with love and respect. Instead of them we now have super-stores, or… more space…

At least his music has survived!

Photos © where specified,

credits specified there where available,

other images from the internet, assumed to be in the public domain.

DISCLAIMER – I don’t claim credit or ownership on the images taken from the internet, assumed to be in the public domain, used here. The owners retain their copyrights to their works. I am sharing the images exclusively for educational and artistic purposes – this blog is not monetized, and has no commercial profit whatsoever. Whenever I find the credits to internet images I am happy to add them. If you are the artist or the owner of original photos/images presented on this blog and you wish your works to be removed from here, or edited to include the proper credits, please send me a message and they will either be removed or edited. Thank you!

Leave a comment

No comments yet.

Leave a comment